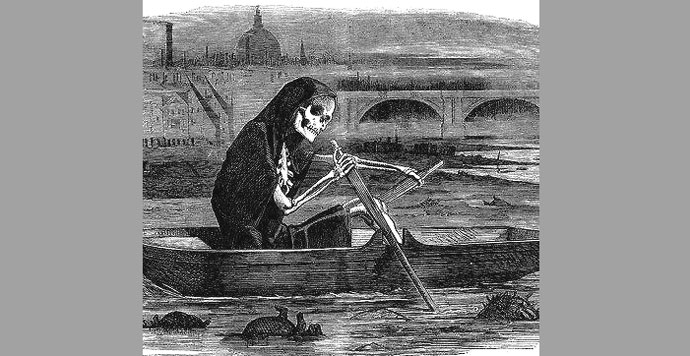

Future generations will react to today’s ambivalence towards road danger in the same way as we recoil at the thought of the open sewers of Victorian London. So says Danny Dorling, a professor from Sheffield University argues road safety is a public health not a transport issue, and until it is properly addressed people will continue to die.

Compared to cancer, and other causes of death, road deaths are falling very slowly. In fact, the most likely way for you to die if you are between the ages of 5 and 30, is being hit by a car. Fear of road danger reduces the number of people cycling and walking, which in turn has detrimental effects on public health – asthma, obesity and stress-related illnesses to name a few.

Professor Dorling compares road danger to the open sewers of the 19th century, or smoking in the first half of the 20th century. Until these dangers were taken seriously as public health concerns, people continued to die. Dorling argues that road danger reduction should be taken out of the Department of Transport and moved in to the Department of Health; road safety needs to be managed by the people concerned with saving lives, not those focused on keeping people moving.

Road danger 2010-2015

Road deaths and serious injuries have since 2010 declined across Britain as a whole. By 2014 there had been a 19 per cent reduction in the number of people killed or seriously injured relative to the average for 2005–9. However, most of this reduction occurred between 2007 and 2010.

Many local authorities are critical of recent changes in policy. While overall casualties declined over this period for all major road user groups (except for cyclists, where the number seriously injured increased) improvements around Britain are patchy. In terms of public policy, the last five years have been notable for cuts in spending, increased devolution and a move in England towards localism – all changes that have had an effect on road danger reduction.

The coalition government failed to set national casualty reduction targets (other than the strategic road network), focussing instead on driver education. This less prescriptive approach to leadership and strategy is summarised in a recent report by the Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport Safety (PACTS)).

There has been support for new enforcement legislation, particularly in drink-driving, but concern that the lack of resources for roads policing would reduce its effectiveness. Other missed opportunities include no Green Paper on young driver safety

Elsewhere in Britain, Scotland managed to reduce the drink-drive limit and Northern Ireland moved closer to a lower limit and the introduction of graduated driver licensing for young drivers.

The voluntary sector is clear that an ambitious new strategy is required in order to reduce road danger over the next five years; a strategy might include better guidance for local authorities to reduce speed limits, improvements in driving standards through improved driver training backed by enforcement campaigns and a fundamental review of traffic laws and sentencing. Bringing dangerous drivers to account must be high up any agenda.

Foe example, presumed liability in civil law makes motorists financially liable for collisions with pedestrians or cyclists. Only when the pedestrian or cyclist is proved to be negligent does the driver avoid paying compensation through their insurance. The principle recognises that the drivers of faster, heavier vehicles have a duty of care, and that if a pedestrian or cyclist is injured in a road traffic collision, injuries or shock may make it difficult for them to accurately recollect the event.

According to the campaign group Roadshare, “Presumed liability in civil law is the proper approach for a mature, socially conscious nation as it addresses the unacceptable human cost of the current system. Under presumed liability, injured vulnerable road users are properly and promptly cared for and not forced to fight for compensation.”

At present, motor insurers routinely argue for reductions in compensation to vulnerable road users injured in road traffic collisions, even in the face of evidence that their customers are at fault.

Even cities in the home of the car are making law to protect cyclists. Los Angeles city council is one of a number of American cities to being in new laws to protect cyclists against harassment by motorists. Such laws discourage dangerous behaviour toward cyclists and provide another tool with which to prosecute offending drivers.

Your journey. Our world

The ETA has been voted the most ethical insurance company in Britain for the second year running by the Good Shopping Guide. Beating household-name insurance companies such as John Lewis and the Co-op, the ETA earned an ethical company index score of 89.

The ETA was established in 1990 as an ethical provider of green, reliable travel services. Twenty six years on, we continue to offer cycle insurance, travel insurance and breakdown cover while putting concern for the environment at the heart of all we do.

0 Comments View now